Patents

In 1973, my high school math teacher Don DeWitt showed a film called The Ron Resch Paper and Stick Thing Film. (“Thing” was dropped from the title in a 1992 re-release.)

The film documents Resch’s exploration of folded-paper structures, beginning with a breathtakingly simple motivation: What happens to a sheet of paper when you crumple it? Exploring this question throughout the 1960s, Resch discovered patterns and regularities in the crumpled sheet, leading him from periodic 3-dimensional tilings and space-filling structures to early computer animations and computer-assisted architectural design (in the era of punch cards and drum plotters). The scope of his patient, physical-modeling-based creativity and curiosity over a decade is stunning; and was, to a certain teenage nerd, incredibly inspiring. I began making paper polyhedron models.

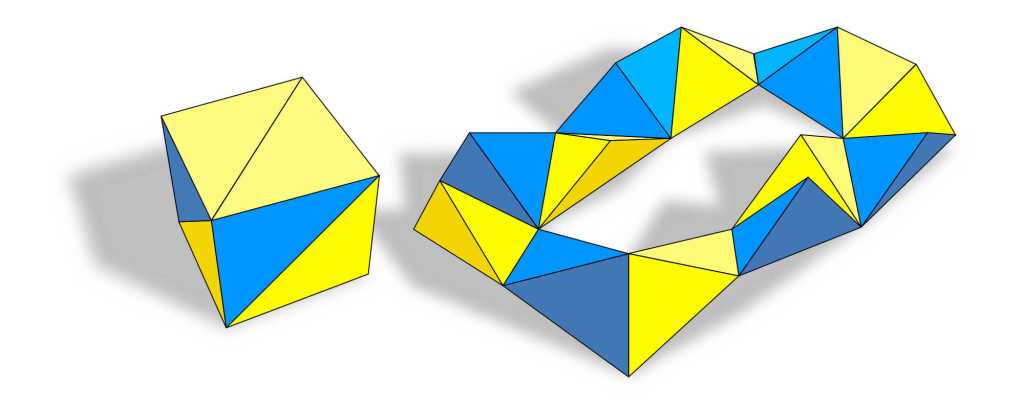

During Christmas break of 1973, I constructed the twelve identical tetrahedrons having a cube’s center as their apexes and the isosceles-right-triangle halves of the cube’s faces as their bases. I handed these twelve pieces to my little sister, age 11, and challenged her to reconstruct the cube, which she did in about four seconds. Clearly this was not a sufficiently difficult puzzle. So, thinking of some of Resch’s models, in which he’d hinged together cubes and other polyhedra to make kinetic sculptures, I began to tape my “cube twelfths” together randomly along various edges. On New Year’s Day 1974, completely by accident — possibly the most miraculous accident of my life — I taped the twelve pieces into a diagonally symmetric loop, a polyhedral necklace. Astonishingly, I was able to fold this necklace inwards with a kind of twist, and the cube was reconstituted.

(When Christmas break was over, I brought this puzzle to school and showed it to Don DeWitt. He fiddled with it for about 90 seconds, failed to reconstruct the cube, and declared, “Jones, you’re obnoxious!” — which was his way of saying that he was astonished and delighted.)

I then tried the same kind of dissection on the regular octahedron and regular tetrahedron. The outer surface of the tetrahedron “necklace”, comprising eight smaller tetrahedrons, amounted to a strip of paper folded into rectangular fourths with a diagonal fold on each fourth, making a “W” pattern.

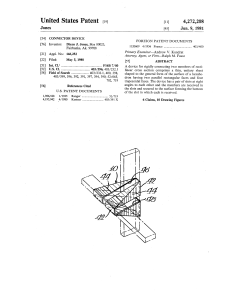

As an undergrad at the Illinois Institute of Technology in the late 1970s, it occurred to me that the tetrahedral “necklace” could be used to brace two mutually perpendicular intersecting half planes.

Well, cutting to the chase: In 1981, the tetrahedral “necklace” became US Patent 4,272,208, a connector device intended to secure two pieces of milled lumber, or two relatively thin sheets of rigid material. I used such connectors made of Strathmore board to create this wall sculpture, which was chosen by the (long defunct) Sales and Rental Gallery of the Art Institute of Chicago for their Silver Anniversary Show in 1979.

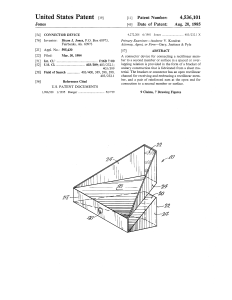

A certain amount of experimentation with paper and sheet-metal models led to a design somewhat more practical for the construction industry, US Patent 4,536,101, in 1985.

In early 1986, a sheet metal firm in Fairbanks, Alaska cut the rectangular blanks and punched the center hole for about 150 “brackets”. I did the bending with homemade jigs and Vise-Grip clamps, then the sheet metal people spot-welded the faces marked “22” in the patent 4,536,101 figure. I used about 100 brackets to build a house, shown in the photos below, having 17-inch-thick walls insulated with fiberglass batts.

NOTE: As of 16 November 2023, I’ve removed most PDF content from this site…and as of 15 June 2025, I’ve disabled most of the external hyperlinks. There’s been too much “activity” by non-humans, for what purposes we can only guess…

Updated 14 January 2026